By Jacob A. Nota, PhD, ABPP

This article describes the results of a 2019 Michael Jenike Young Investigator Award, an IOCDF funded research project.

SUMMARY

- Research has shown that differences between circadian rhythms (“biological clocks”) and the time when people go to sleep may be associated with OCD symptom severity.

- Melatonin is a hormone that is produced by the body before sleep and regulates the daily sleep-wake cycle.

- 23 participants with OCD who underwent intensive residential treatment took part in a study that measured melatonin production to understand whether differences in circadian rhythms and when people go to sleep are related to OCD severity.

- During four weeks of intensive residential treatment, the production of melatonin began to happen earlier on average. The time when patients went to sleep, their length of sleep, and their circadian rhythms shifted toward general population averages.

- More research into sleep and OCD is needed, as there are still questions about exactly how differences in sleep may affect OCD symptom severity.

Wait…birds with OCD? Well, animal models of OCD (e.g., in mice) do exist and help us learn more about how obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) develops, is maintained, and can be treated. In this case though, we are talking about “night owls” and “morning larks.”

These terms describe people whose biological clocks are programmed to feel and function best earlier (larks) or later (owls) in the environmental day. Variability in functioning across the day has been studied for decades, but whether differences in one’s biological clock — circadian rhythms — are related to psychopathology has only begun to be examined. In individuals with OCD, there is evidence that differences in sleep behavior and biological clocks may be associated with symptoms and responses to existing treatments. Work examining these relations is carried out across the globe and garnering more attention, as more research publications and presentations are being published year after year.

The IOCDF’s Young Investigator Award program just completed its support of my project, which examined circadian rhythms of melatonin (a hormone associated with the sleep-wake cycle) production in individuals undergoing intensive residential treatment for OCD. With the support from the IOCDF, my team recruited 23 individuals to participate in a study where the timing of their bodies’ production of melatonin was measured at four time points during their residential treatment. Typically, diurnal species like humans produce essentially no melatonin during the daytime and have a rapid onset of melatonin release in the evening, usually a couple of hours before they fall asleep. Melatonin production is suppressed by bright light (like sunlight), and so the saliva samples collected in our study were collected in dim light. This allowed us to determine the time of onset of melatonin production, which is known as the dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) and represents the transition of one’s biological clock from “daytime” mode to “nighttime” mode. In “daytime” mode, our bodies are organized to interact with the environment and gather what we need (e.g., solve problems, maintain relationships, eat, etc.). In “nighttime” mode, our bodies are organized to focus on internal processes (e.g., restoring, cleaning, consolidating memories, etc.).

My team adapted a method for estimating when participants would produce melatonin and then collected saliva samples to capture the moment when their bodies actually started producing it. This was a first in residential treatment for OCD and was highly successful (98% of samples collected passed quality control checks, and DLMO was identified in 82% of the acceptable-quality samples). As a pilot study, this demonstrates that this process of collecting data is effective, reliable, and valid.

Adding these DLMO data to established self-report measures of sleep/wake behavior, we were able to observe the way that sleep behavior and biological clocks changed over the course of residential treatment. Average sleep duration at admission to treatment was 7 hours and 17 minutes. This average increased slightly by the second week of treatment (7 hours and 22 minutes), and then again by the fourth week of treatment (7 hours and 36 minutes). At the time of admission to treatment, participants were going to bed close to midnight (11:58 PM), which shifted earlier by the second week (11:05 PM), and earlier still by the fourth week of treatment (10:46 PM). At admission, patients’ average DLMO was at 10:38 PM, which is approximately one hour later than that estimated in the general population (Burgess et al., 2003) and overlapped with populations with clinically significant delayed sleep/wake schedules (Reis & Paiva, 2019).

However, by the second week of treatment, their average DLMO shifted earlier to 9:45 PM, and remained earlier than at admission at the fourth week (10:06 PM); at the time of discharge, it was at its earliest (9:25 PM). Together, these data indicate that sleep duration, timing, and biological circadian rhythms shifted toward general population averages across residential treatment. Our team hypothesizes that the shifts in DLMO times were due to supported bed and wake times during treatment (e.g., curfew, scheduled morning groups). Whether these changes are associated with the effect of treatment on OCD symptoms is yet to be determined.

I previously hypothesized that misalignment between one’s biological circadian rhythms and the environment’s demands can maintain symptoms of psychopathology. I’ve called this a “second hit” model (Nota et al., 2015; Nota et al., 2016) where vulnerabilities (the first “hits”) in attention and cognition that are associated with OCD (e.g., response inhibition, set-shifting, etc.) are specifically affected (the second “hits”) by sleep disturbance and circadian rhythm misalignment.

In this study we defined alignment between circadian rhythms and daily schedule using midpoint of sleep phase angle (Mid-PA). Mid-PA measures the gap between one’s body shifting to “night” mode (i.e., DLMO) and the midpoint of the period of sleep for the night. There is always a gap between these, and a larger gap is associated with better alignment between your circadian rhythm and your sleep/wake schedule, as one is therefore sleeping during the time their body is “programmed” to do so and interacting with the environment at the time their body is most prepared to do so.

For our final analyses of these pilot data, we looked for hints as to whether changes in biological clocks could potentially affect OCD symptoms by first examining whether such changes preceded changes in OCD symptoms during residential treatment. We used a specialized data analysis called a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM). This type of model cannot determine whether the changes in either clocks or OCD symptoms cause changes in the other, but can test whether changes in one reliably predicts anything about subsequent change in the other. This analysis is important because if changes in OCD symptoms can be predicted by alignment of circadian rhythms with the environment, future experiments could test whether shifting the internal clock could help patients with OCD.

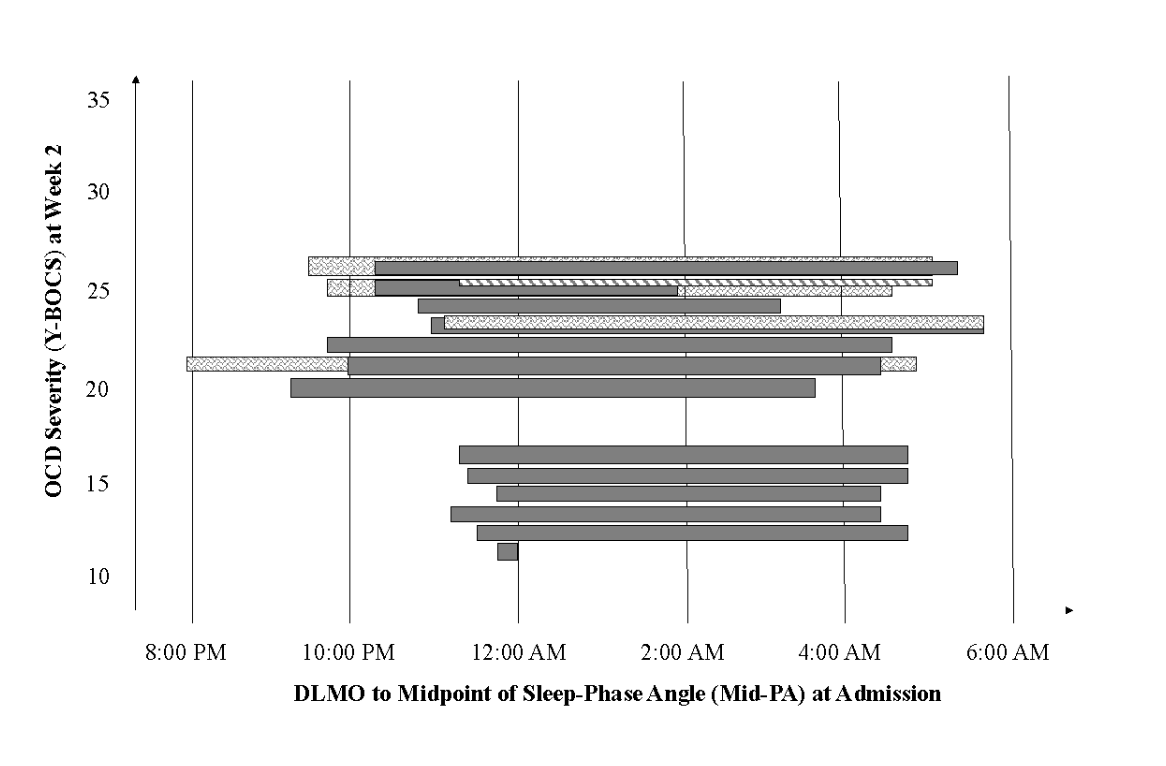

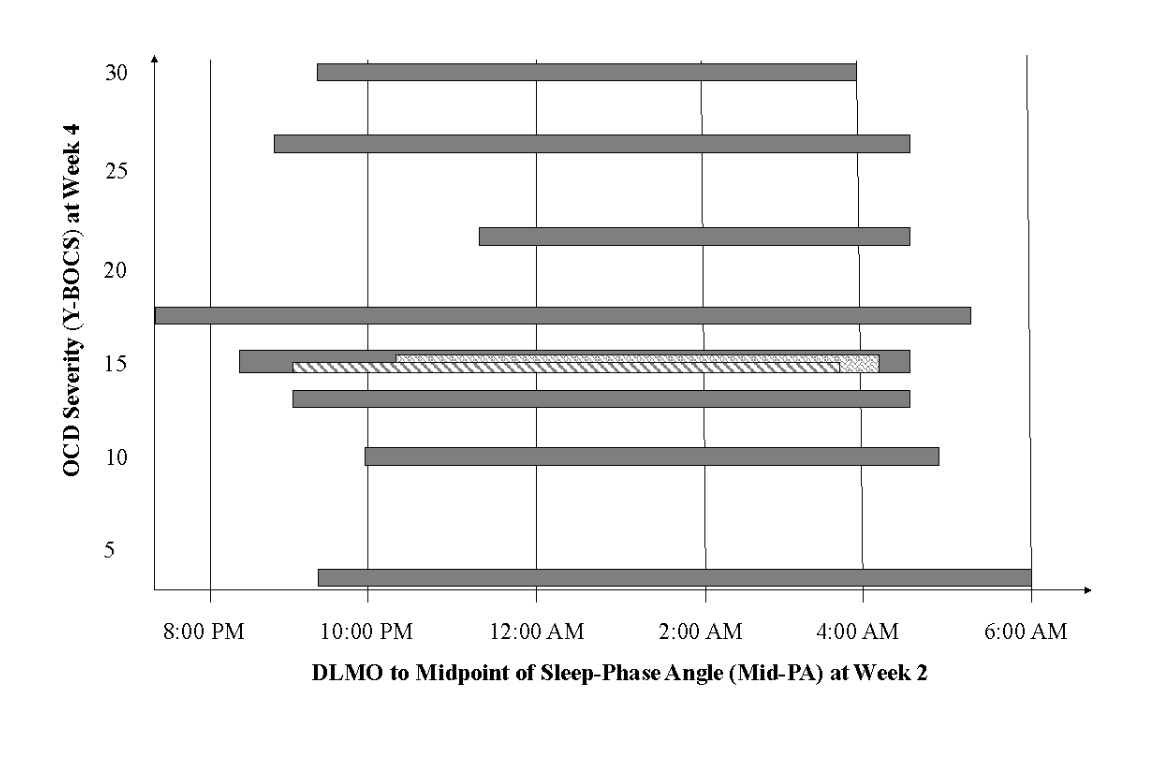

We modeled the relations between Mid-PA and OCD symptoms across the first four weeks of treatment and identified a significant cross-lagged path between Mid-PA and OCD symptom severity. This suggests that shorter phase angle at admission (a smaller gap between your body shifting to “night” mode and the midpoint of your sleep for the night, indicating poorer alignment between your circadian rhythm and the environment) was associated with less severe OCD symptoms at the second week of treatment (Figure 1). In other words, individuals who had the shortest phase angle at admission were the ones who had the least severe OCD symptoms at the second week of treatment. Interestingly, this pattern then reversed in the next weeks, with shorter phase angle at the second week of treatment being associated with more severe OCD symptoms at the fourth week of treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Relation between dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) to midpoint of sleep-phase angle (Mid-PA) at admission to treatment and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) symptom severity at the second week of treatment. Each bar represents one individual’s data; the left-most end of each bar represents DLMO and the right-most end of the bar represents the midpoint of their sleep. Shorter Mid-PA represents poorer alignment between biological circadian rhythms and daily sleep-wake schedule. Cases were plotted in order of OCD symptom severity. The inverted pyramid shape demonstrates how shorter Mid-PA at admission predicts less severe OCD symptoms at week two of treatment.

Figure 2. Relation between dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) to midpoint of sleep-phase angle (Mid-PA) at second week of treatment and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) symptom severity at the fourth week of treatment. Each bar represents one individual’s data; the left-most end of each bar represents DLMO and the right-most end of the bar represents the midpoint of their sleep. Shorter Mid-PA represents poorer alignment between biological circadian rhythms and daily sleep-wake schedule. Cases were plotted in order of OCD symptom severity. The pyramid shape demonstrates how shorter Mid-PA at week two of treatment predicts more severe OCD symptoms at week four.

These observed relations between Mid-PA and OCD symptoms justify the need for further study of biological clocks, especially in relation to one’s environmental demands, sleep behavior schedule, and OCD symptom severity. We interpret the inconsistent direction of this relation across treatment as suggesting that future studies will need to think carefully about how biological clocks change (e.g., in response to exposure to light, activity, etc.) and environmental demands change (e.g., starting a new treatment program, engaging in specific tasks in treatment like exposure and ritual prevention, etc.). More specific hypotheses need to be made about the effects on physical and cognitive resources that may boost or limit treatments. These data are just the beginning, and I am excited to share these findings and use them to design our next studies.

The Young Investigator Award program has been crucial to the project and associated work that is advancing our understanding of the relation between sleep, biological clocks, and OCD. I received two other grants related to this work and published multiple peer-reviewed articles from the line of research during the time I was supported by this award. My team has formed multiple collaborative relationships with other researchers and research sites that will enable us to continue this work, and I intend to continue collaborating with the IOCDF for the rest of my career as a clinician and researcher. I am currently submitting a peer-reviewed publication based on this project, and plan to present about the study and my other work at the IOCDF Annual Conference this July in San Francisco, CA. I look forward to connecting with anyone who is interested in my line of work!

Jacob A. Nota, PhD, ABPP is a Staff Psychologist at McLean Hospital’s Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Institute in Belmont, MA. There, he engages in a program of clinical and translational research. His specialty is in the intersection between sleep, circadian rhythms, and anxiety disorders. He received the IOCDF’s Young Investigator Award in 2019. He is also the Owner/President of Overbrook Counseling Services, P.C. in Arlington, MA. Dr. Nota treats individuals with obsessive compulsive and related disorders and anxiety disorders using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), including exposure and ritual prevention (ERP) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

References

Burgess, H.J., Savic, N., Sletten, T., Roach, G., Gilbert, S.S., & Dawson, D. (2003). The relationship between the dim light melatonin onset and sleep on a regular schedule in young healthy adults. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 1(2), 102-114.

Nota, J.A. & Coles, M.E. (2015). Duration and timing of sleep are associated with repetitive negative thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39, 253-261.

Nota, J.A., Schubert, J.R., & Coles, M.E. (2016). Sleep disruption is related to poor response inhibition in individuals with obsessive-compulsive and repetitive negative thought symptoms. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 50, 23-32.

Reis, C., & Paiva, T. (2019). Delayed sleep-wake phase disorder in a clinical population: gender and sub-population differences. Sleep Science, 12(3), 203-213.