The best answer to this question is "we don't fully know" and that "there is no single cause."

OCD is a complex problem that likely has a combination of causes. In fact, the causes of OCD for one person might be different than the causes for another. Fortunately, effective treatment for OCD is available despite our uncertainty about its causes.

Still, plenty of research has been conducted about what factors might be involved in the cause of OCD. For decades, studies have shown a multitude of factors — sometimes in combination — that can contribute to the development of OCD. Here is some information you might find interesting:

Is OCD a Brain Disorder?

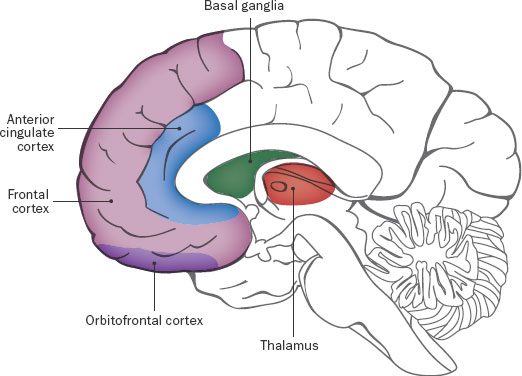

Images of the brain have revealed some differences between people with OCD and those without it, but these differences are small and not consistently observed. It is challenging to interpret what these findings mean. This is partly due to a "chicken and egg" issue: many brain imaging studies don't clarify whether these differences cause OCD or are caused by OCD.

Research has shown that parts of the brain affected by OCD include the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the thalamus, and the basal ganglia [1]. The OFC is involved in shaping our thoughts, memories, emotions, and intuitive/gut feelings - also known as "visceral states." The ACC helps us detect or predict errors, and plays a role in attention, motivation, memory, and emotion. The thalamus sends signals to the brain that relate to physical movement and sensation [2]. The basal ganglia helps us plan and carry out our actions and behaviors [3]. Overactivity in these parts of the brain has been found in people with OCD [4].

Is OCD Caused by an Imbalance of Serotonin (or Other Neurotransmitters)?

While medications like serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) can help reduce OCD symptoms, there is no conclusive research evidence that OCD is caused solely by a dysfunction serotonin levels, or of other neurotransmitters (chemicals found in the brain and other systems of the body). The idea that "chemical imbalances" are the only cause of OCD is outdated and too simplistic.

However, an imbalance in neurotransmitters can play a role in OCD, with strong evidence that serotonin is implicated [5], [6]. Research has also shown that differences in the neurotransmitters dopamine, glutamate, and GABA can also contribute to the progression of OCD.

Is OCD Inherited?

Studies show that OCD can run in families: between 10%-20% of children who have a parent with OCD will develop OCD themselves (but 80%-90% will not), though we must be careful not to simply assume that this is caused by genetics [7]. For example, many learned traits also tend to run in families, such as what language is spoken and family religious beliefs. For this reason, researchers believe that a combination of genes and environmental factors play a role in the development of OCD [8].

Is OCD Caused by Environmental Factors?

As with the guesses about genetic causes of OCD, there is no definitive evidence that OCD is a learned behavior or is solely caused by environmental factors. A study with twins showed that genetics had a stronger role than environmental factors in the expression and development of OCD, and that a shared environment (like a home) did not significantly impact OCD expression. However, non-shared environments did have a small effect [9]. The environment a person is in and interacts with plays some role, since the types of obsessions and compulsions that people have differ for members of different cultural, ethnic, sexual, and religious groups [10]. Moreover, the themes of obsessional fears tend to change over time: in the 1980s, for example, there was an increase in obsessions related to HIV/AIDS, which coincided with the spread of this disease [11], [12]. A similar phenomenon has taken place during the recent COVID-19 pandemic [13].

What About PANDAS/PANS?

PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections) and PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) are disorders related to OCD that occur in childhood following the body’s reaction to an infection. PANDAS is associated with Group A Streptococcus - the bacteria responsible for strep throat and other serious infections [14]. PANDAS and PANS look very different from other forms of childhood OCD, with the most obvious difference being that they happen very suddenly; the child develops symptoms seemingly overnight that have a very severe impact on their life. It is important to understand that because of the way PANDAS/PANS are diagnosed based on retrospective self- (or parent-) reporting, it is not possible to know for sure that the OCD symptoms were caused by an infection.

For more information on PANDAS, including diagnosis and treatment, click here.

Future Research

Although we do not currently know what causes OCD, conducting research is the key to figuring out the precise factors involved, and understanding how they work together. The IOCDF provides funding support for researchers in the OCD and related disorders field through the IOCDF Research Grant Program. The IOCDF also hosts the Annual IOCDF Research Symposium, an event that takes place each year the day before the Annual OCD Conference.

Read more about our research efforts.

Learn More About OCD

Sources:

- [1] Pittenger, C. (Ed.). (2017). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: phenomenology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Oxford University Press. ↩

- [2] Huey, E. D., Zahn, R., Krueger, F., Moll, J., Kapogiannis, D., Wassermann, E. M., & Grafman, J. (2008). A psychological and neuroanatomical model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 20(4), 390–408. doi:10.1176/jnp.2008.20.4.390 ↩

- [3] Huey, E. D., Zahn, R., Krueger, F., Moll, J., Kapogiannis, D., Wassermann, E. M., & Grafman, J. (2008). A psychological and neuroanatomical model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 20(4), 390–408. doi:10.1176/jnp.2008.20.4.390 ↩

- [4] Huey, E. D., Zahn, R., Krueger, F., Moll, J., Kapogiannis, D., Wassermann, E. M., & Grafman, J. (2008). A psychological and neuroanatomical model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 20(4), 390–408. doi:10.1176/jnp.2008.20.4.390 ↩

- [5] Graat, I., Figee, M., & Denys, D. (2017). Neurotransmitter dysregulation in OCD. In C. Pittenger (Ed.) Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Phenomenology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Oxford University Press. ↩

- [6] Derksen, M., Feenstra, M., Willuhn, I., & Denys, D. (2020). Chapter 44 — The serotonergic system in obsessive-compulsive disorder. In C. P. Müller & K.A. Cunningham (Eds.). Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Elsevier. ↩

- [7] Browne, H. A., Gair, S. L., Scharf, J. M., & Grice, D. E. (2014). Genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 37(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2014.06.002 ↩

- [8] Mataix-Cols, D., Boman, M., Monzani, B., Rück, C., Serlachius, E., Långström, N., & Lichtenstein, P. (2013). Population-based, multigenerational family clustering study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA psychiatry, 70(7), 709-717. ↩

- [9] Krebs, G., Waszczuk, M. A., Zavos, H. M., Bolton, D., & Eley, T. C. (2015). Genetic and environmental influences on obsessive-compulsive behaviour across development: a longitudinal twin study. Psychological medicine, 45(7), 1539–1549. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002761 ↩

- [10] Williams, M. T., Chapman, L. K., Simms, J. V., & Tellawi, G. (2017). Cross-cultural phenomenology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In J. Abramowitz, D. McKay, & E. Storch (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (p. 56-74). Wiley. ISBN: 978-1-118-88964-0. ↩

- [11] Fisman, S. N., & Walsh, L. (1994). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and fear of AIDS contamination in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(3), 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199403000-00008 ↩

- [12] Bruce, B. K., & Stevens, V. M. (1992). AIDS-related obsessive compulsive disorder: A treatment dilemma. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 6(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(92)90028-6 ↩

- [13] Dennis, D., McGlinchey, E., & Wheaton, M. G. (2023). The perceived long-term impact of COVID-19 on OCD symptomology. Journal of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, 38, 100812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2023.100812 ↩

- [14] Thienemann, M., Murphy, T., Leckman, J., Shaw, R., Williams, K., Kapphahn, C., Frankovich, J., Geller, D., Bernstein, G., Chang, K., Elia, J., & Swedo, S. (2017). Clinical Management of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Part I-Psychiatric and Behavioral Interventions. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 27(7), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0145 ↩